With autonomous vessels, particularly tugs, being a common topic of debate and discussion recently, we decided to approach tug design leader Robert Allan Ltd (RAL), which already has a number of autonomous projects underway, to get the company's thoughts on the technology, and in particular what RAL is working on.

Vince den Hertog, Vice President, Engineering at RAL, was kind enough to give us his thoughts.

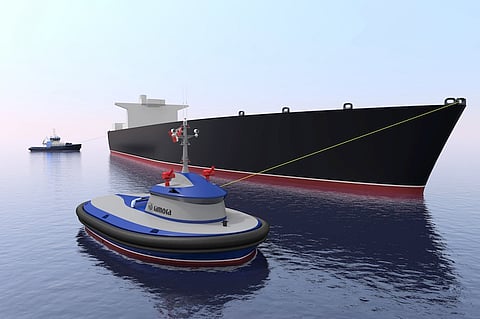

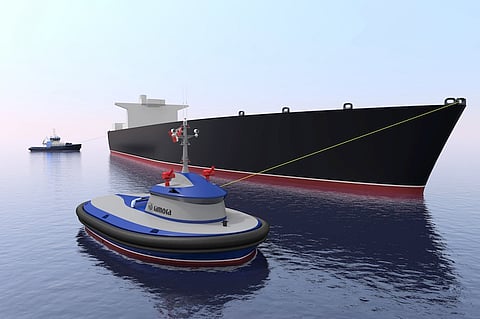

At many ports in the world, inbound ships are met by two or more ship-handling tugs that connect to the ship with their towlines while the ship is underway, typically one at the bow and another at the stern.

Under the direction of a pilot on board the ship, these tugs assist the ship with turning and braking manoeuvres until the ship is safely docked. The bow tug, which operates ahead of the ship, is exposed to some risk of being hit by the ship's bow or pulled over by its own towline if things go wrong.

With ships getting larger, these risks increase as minimum manoeuvring speeds creep upward. The RAmora series of tugs are highly manoeuvrable for bow tug operations by virtue of its fore and aft Voith Schneider propulsor (VSP) arrangement, and of course have no people on board.

With the fore/aft arrangement of the VSPs based on Robert Allan Ltd.'s RAVE series of tugs, RAmora can travel in any direction and orientation.

This immense controllability is ideal for un-crewed operations since a computer-based control system is able to seamlessly vector the thrusts from both VSPs to execute a manoeuvre almost instantaneously.

This nimbleness is a real asset for higher speed bow tug operations. On RAmora, we've also been able to place the towing point near midships where the highest towing forces can be generated.

This is not easy to do on conventional tugs since the deckhouse and wheelhouse get in the way. Compared to a conventional tug, RAmora is actually rather sparsely equipped since crew accommodations, domestic systems or safety equipment are no longer needed.

To transfer the towline to the ship underway, RAmora is equipped with a motion-compensated line transfer crane that essentially hands the end of the towline to the ships crew.

While RAmora is not designed to save money by replacing crew, we expect cost reductions are possible where labour costs are particularly high, especially where tugs are operating in remote ports.

One challenge was actually shedding our conventional thinking about how a tug and its towing-related deck equipment should be arranged.

The RAmora design became an exercise in simplification. With no crew on board to fix things, un-crewed vessels need to be reliable. This means that machinery and equipment need to be as basic as possible without giving up capability.

The other significant challenge is towline connection and retrieval. We had actually considered magnetic or vacuum pad systems to attach the tug to the ship, however this would require the tug to operate too close to the ship to be effective at pulling. The wash from the thrusters would simply impinge on the side of the ship reducing pull compared with operating farther away at the end of a towline.

Besides, we saw no reason to change how ship-handling operations are done with towlines provided that we could solve the towline connection problem.

The use of a crane to pass a towline is not a new idea. Some of our tugs were equipped with knuckleboom cranes to pass towing hawsers in Vancouver, doing this in the 1970s.

Other companies are looking at the same problem. There are concepts to use drones to pass messenger lines. Svitzer has been trialling a line catcher system.

Tug masters that we've been working with have expressed a clear preference for operating RAmora from a shore-based operations room with plenty of elbow room and no outside noise or visual distractions.

We had considered placing the RAmora operator on a conventional tug working in tandem with RAmora, but the tug masters feel this would introduce an undesirable dissonance between how RAmora motions are perceived by an operator by video and the motions that are actually experienced on board the conventional tug.

In any case, the only person the tug masters are interested in communicating with during ship handling operations is the pilot on-board the ship issuing instructions.

A shore-based operation room that is otherwise quiet and free of motion altogether turns out to be the best environment for a master to communicate and concentrate.

The control system will have a fault management system that will be pre-programmed to execute the most appropriate response to a given fault, depending on what RAmora is doing at the time.

Not yet. RAmora is a design only at this point. There have been some technology demonstration where conventional tugs have been temporarily equipped to allow a basic level of remote operation, but none that we are aware of involving the kind of bow tug ship handling service RAmora is designed for.

The lesson we have learned is that in the years to come we can expect more control and communication options to become available for different workboat applications.

We may soon be at point where complete control and communication system packages for remote operation will be available as turn-key systems from various third party suppliers. And the level of autonomy they offer may be scalable.

As naval architects, our focus can remain on where we can add the most value, that is on working with clients to define the functional requirements for the control and communication system for the application and designing the best un-crewed workboat platform for the job, whether it's a tug, fireboat, spill response vessel, ferry or something completely new.